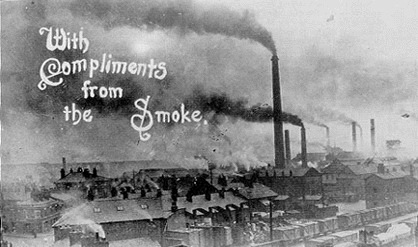

That’s Widnes there, the chemical town where I was born. There are several versions of this photograph in circulation, and this is the mildest. The others have had additional smoke added: perhaps the photographer knew of worse places, and wished to compete. I came along some 12 years after the Clean Air Acts, and still had acute bronchities and asthma throughout my childhood.

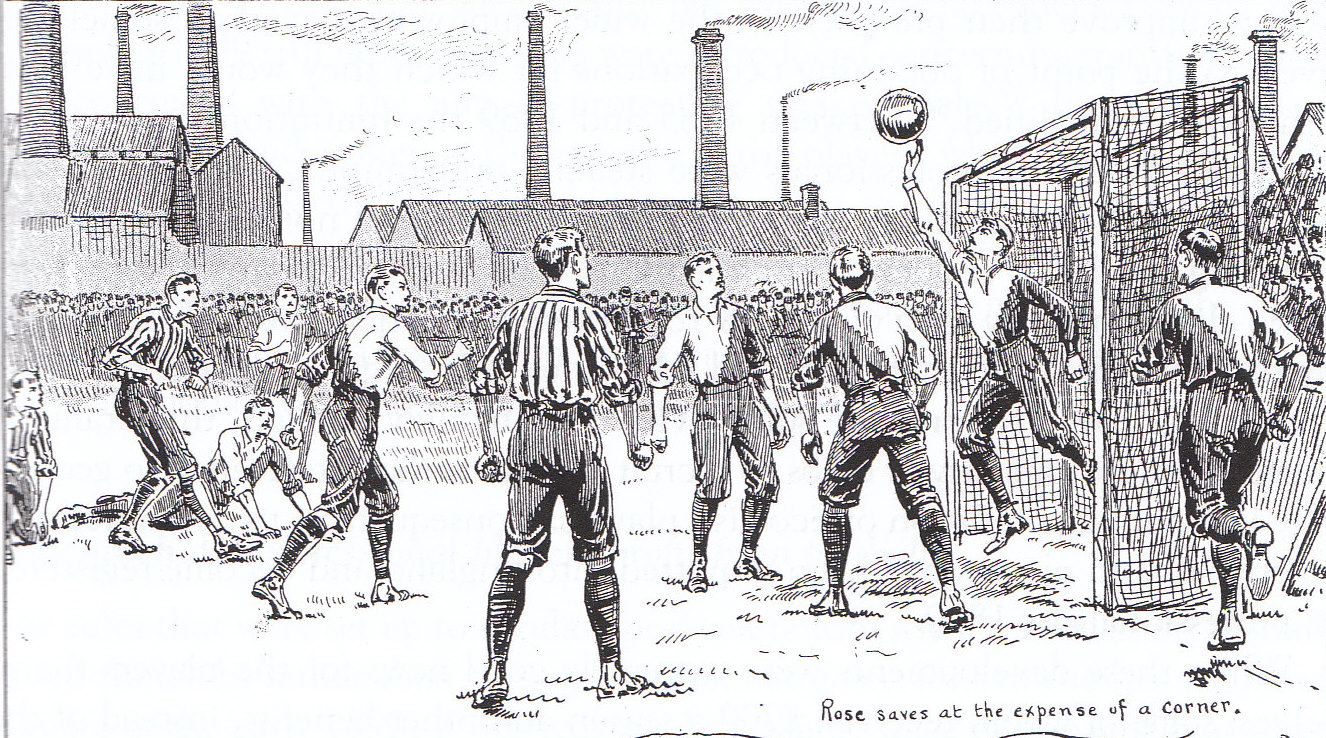

Football training in the Victorian and Edwardian periods is subject to an urban myth, one you’ll recognise straightaway: starve the players of the ball during the week, coaches are meant to have said, and they’ll be all the hungrier for it on Saturday afternoon. I’ve never been able to trace the origins of that saying, and I think it’s apocryphal. In its favour is the fact that where a club did possess a trainer, the very newness of the sport of professional football meant that he was likely to have been poached from boxing etc.; against it are the several exceptions to the no-football rule such as Fulham or Manchester City.

It is true, however, that there was less training – an intense pre-season could be followed by as little as two hours of activity per day between October and March. Professional footballers were not as fit in the modern sense as they would become after the 1950s.

Overtraining has always been a concern for footballers, and in the Victorian and Edwardian periods there would have been another consideration: safety. In the circumstances of the average Football League Division One club, factors outside the control of club or players placed limits on the amount of safe training that could be attempted. Background; working class men had been brought up on poor diets. The risk of injury: professional careers were shorter then, competition for places was fierce, and future prospects few, meaning that players would, in their own interests, attempt to avoid getting hurt. And then there was the quality of the air. Smoke.

They became Manchester United of course. Newton Heath’s ground at Clayton was famously smoky, but, as in the case of Widnes, it takes imagination these days to capture any sense of what that actually meant. In particular, the smell of coalsmoke, which would have predominated, is remembered only by the over-50s now.

You can get a sense of it by visiting Dennis Severs’ house in Spitalfields, and heading all the way upstairs to the “impoverished weavers’ quarters”. It’s perhaps the most depressing room in any museum space in the United Kingdom. The bone-coldness, the despair, the pathetic half-rotting vegetables they have for food, and the exhausted, stinking fire must leave most visitors in need of drinks and loud music.

But the cabbage smell doesn’t catch at the back of your throat, or linger like some ancestral memory, in the way the coal fire does. You can still meet it for real in Highland villages like Luss on the shore of Loch Lomond; once it was the common smell of every major town and city in our nation. Once you’ve got the sense of it, imagine running in it…

The earliest grounds, like Bramall Lane, were opened after twenty years of industrialization had smoked-out the cities, and so they were placed on the outskirts within view of fields and trees. But building soon caught up with them. Many later grounds, Clayton included, had to go where there was affordable space, and that might mean a patch of land too poor even to put a factory on it.

Manchester United moved out of Clayton as soon as funds allowed, although the need to be close to their audience ruled out anywhere terribly sylvan. Even those grounds well enough placed to last, such as Bolton’s Burnden Park, suffered the ill effects of the urban environment.

Let’s take a look around Burnden Park. It was a top rank stadium, hosting the 1901 FA Cup Final replay, and yet – just look at that chimney. In the Mitchell and Kenyon film of this game, it begins to emit at some point during the first half, and its smoke billows out along the top of the main stand and over onto the pitch. It wasn’t the only source of smoke during the match:

That’s a freight train in the background – the line runs immediately above and behind the ground. On a wet day such as this one, the smoke would have been driven down pitchwards. But that’s still not all:

Here’s the view opposite the main stand. It speaks for itself. Another industrial building, more chimneys, and deflectors keeping the smoke down just where, as a player, you’d want it heading safely up.

For the modern viewer, memories of the Beijing Olympics fill in the details. Even after multiple factory closures, even after massive slum clearance in the city (a crime for which the victims are yet to be compensated), many competitors reported severe problems with smoke inhalation.

All of this would impose a powerful set of restrictions on how much training, and how much exertion, a player was capable of enduring and producing. Because the smoke was ever-present, and, by and large, accepted and unnoticed, the chances are that the restrictions were not experienced as restrictions: the players and trainers probably felt, merely, that they were performing close to the maximum levels possible for young men in that sport.

I haven’t mentioned tobacco smoke. Most of the Mitchell and Kenyon football crowd clips show a clear majority of men smoking, usually pipes (cigarettes are there, of course, but they got their big break in the 1914-18 War and in the Victorian and Edwardian period Peterson and co. held the field). Pipe smoke is different from cigarette smoke: it’s thicker, and it lingers considerably longer (which is why pipes were frowned upon in restaurants many years before the smoking ban came in tout court).

How much a pipesmoking crowd would interfere with the players’ lungs during a game is hard to work out. Pipesmoke, like coal smoke, was ubiquitous, the deodorant of the Edwardian male. It was just there. In 2009, Edinburgh’s buses don’t use clean fuel and modern engines as London’s do, and the difference is obvious. It wouldn’t have been in, say, 1995, when I can remember exhaust fumes on the Embankment inducing fainting in vulnerable passers-by.

There is more to be said about fitness in this period – how did players compare with the manual workers who watched them, for instance? And there’s Richard Sanders’ point, raised in his excellent new history of the birth of football, Beastly Fury – how did working-class professionals stack up against the likes of Corinthians?

Whatever the answers to these further questions turn out to be, one thing is clear. There were ceilings to fitness in Victorian and Edwardian football clubs, and they had nothing to do with laziness, primitive attitudes or hunger for the ball. You can send Arsene Wenger, Clive Woodward, Seb Coe and whomever you like back through time to take training sessions in a town like Bolton or Manchester. But what difference would it make? There is only so much you can do when you can’t breathe for the smoke.

I heard about an old boy returning to Cambridge for the first time in 60 years, for a college reunion. He said that he’d not known that there were so many beautiful buildings – after all, they were all black when he was there. And Cambridge was just a market town.

I do have clear memories of London fogs and smogs, though I am not sure that ‘clear’ is the right word. Scarf over nose and mouth and avoid that lamp-post! It was like drowning in M R James. And there weren’t that many factory chimneys in London. And football matches in the fog too, when you could not see to the far side of the pitch.

Odd how these things become part of the romance of the game.