New technology and the new sport of Association Football just seemed to go together in the last years of the nineteenth century. Not only was the modern game as we know it born in amongst cutting-edge manufacturing and mining in the English and Scottish industrial urban towns, not only did the arrival of telegraph, telephone and railway make a modern league system possible, not only did improvements in printing and papermaking enable the pink and green ‘uns, but new ideas used the game to show themselves off to a wider world.

1878 was the year of Swan’s patent for the incandescent light bulb. Although that was the realistic starting point of modern electric lighting, Swan was famously not the only researcher on the case – one occasionally hears Edison’s name in this connection – and public experiments and demonstrations went on all the time.

The 1870s was also the decade in which the new football clubs, especially the pioneers in Sheffield, were discovering themselves as a source of revenue from their paying spectators. Football being a winter game, even the fresh availability of Saturday afternoon wasn’t the perfect answer to the problem of getting the biggest possible crowd. In November, December and January, in foggy, smoky cities, a 3 o’clock kickoff, timed to give men the chance for a post-work meal and drink before making it to the ground, was often too late, darkness closing in well before five. (We’ve looked at this issue here before, and found evidence of 2pm and 2.30pm kickoffs aplenty as late as the 1950s).

There was every reason, therefore, for clubs to experiment with artificial lighting. What impresses is just how well they got on, how early, and how well the businesses behind the lighting experiments took their opportunities.

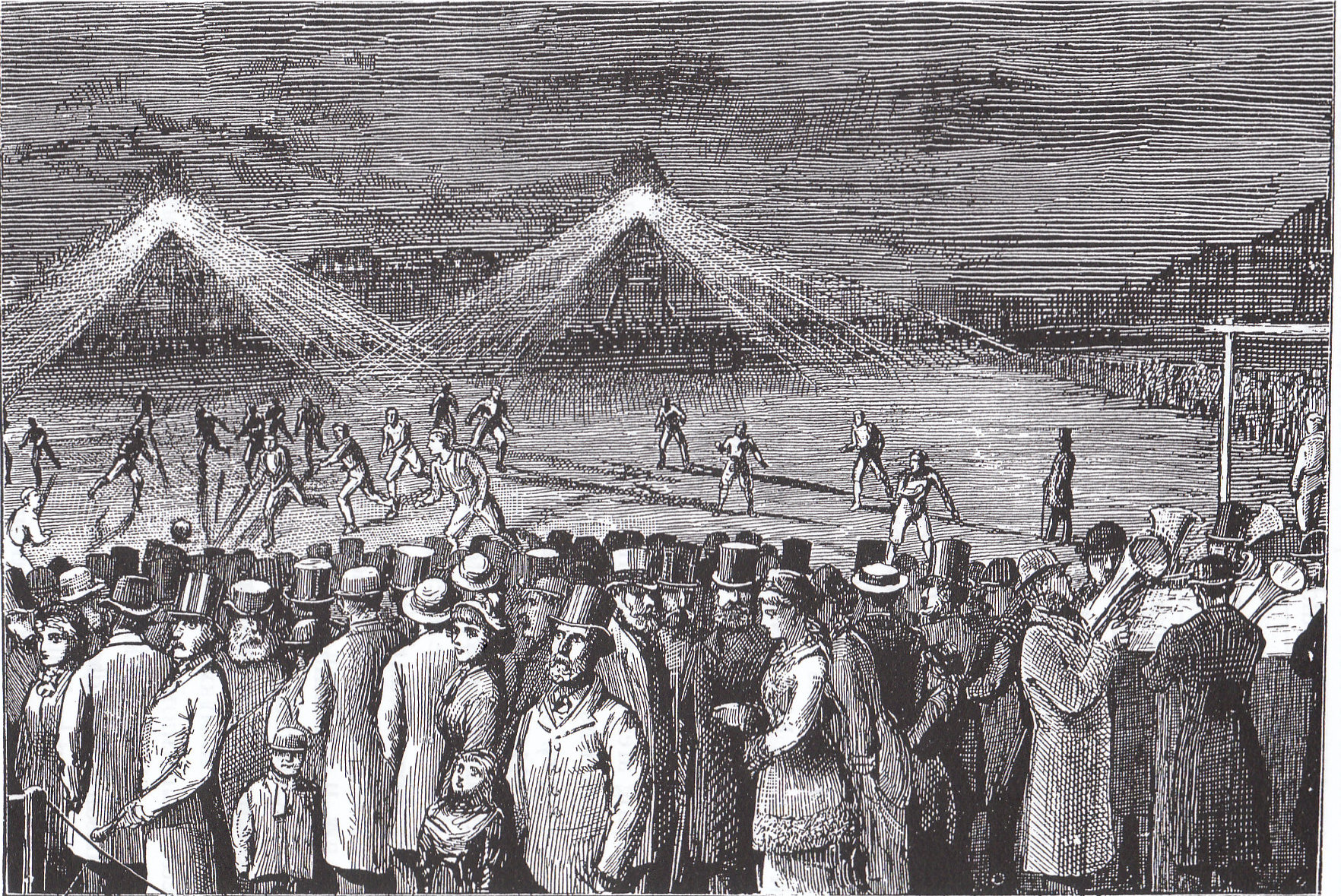

The first floodlit match we know about took place on the 14th October 1878 at Bramall Lane, Sheffield, between teams selected by the Sheffield Football Association from local sides. Football in Sheffield in the 1870s was far further developed towards a recognisable modern form than elsewhere, and the city was a logical choice for the first attempt. This was followed by a poorly-received floodlit match at the Kennington Oval, and then something more interesting at the Powderhall Grounds in Edinburgh on November 11th.

The interest in the Edinburgh match lies in the choice of teams. One was a select Edinburgh FA XI. The other team was Hibs.

Hibernian have always been an Irish team. What that meant for them in 1870s Edinburgh was what it meant for all of the relatively poor Irish community, which clustered around the cheap, insanitary Cowgate and Grassmarket : prejudice and isolation. Hibs had their start from an inspirational, hardworking Irish Catholic priest, but even the best of men from that background had trouble receiving acceptance from the local sporting bodies, who were keen to remain Protestant monopolies. Neither the Scottish FA, nor the Edinburgh FA wanted to know, during Hibs’ hard early days, and actual fixtures proved hard to arrange.

So a match against an Edinburgh FA XI represented a real advance, and an opportunity to break out of an imposed ghetto situation. How this was arranged, and how the London lighting company E. Patterson got involved, isn’t clear. But Hibs’ breakthrough happened under the lights.

Five lights altogether: three at the west end of the ground, and two at the east, reckoned to total 6,000 candles altogether. Forty years to the day before the armistice to end World War One, at 7.30 pm, Hibernians ventured into the spotlight in front of 500 people who’d braved the dark, the cold and a snowstorm to see them take on the Edinburgh XI. That the lights proved to work was a sign that Hibs luck was changing: their 3-0 victory was another.

One light at each end would fail as the game progressed, but the others proved up to the task. In the 1890s, West Ham (as Thames Ironworks) would test floodlighting almost to destruction, and they whitewashed the ball periodically to keep it visible. Did Hibs? In a snowstorm? Probably not..

When the Football League was founded, ten years later, the potential for floodlighting evening matches was known, and rejected only on grounds of its perceived unreliability and the pressing need to ensure that games would be completed. FA and League cultural and technological conservatism wouldn’t really set in until after World War I. So one has to wonder: had Swan and his fellow pioneers arrived just ten years earlier, would league football have been – as Speedway became during the interwar years – an evening mass audience sport, not an afternoon one? Would we still have had to wait until the Busby and Cullis era for floodlit games to become accepted?

The link between football and new technology seems to break in 1914-18. But then, footballing innovation tout court seemed to go the way of the Footballers’ Batallion, Herbert Chapman and a few stadium enlargements aside. Whereas moving pictures seized on football immediately – one of the first clips taken in the UK shows West Brom playing Blackburn – the earliest colour film of the game is late enough to show a 1940s wartime match at Burnley. Radio took an interest, sure, but only in the face of FA and League suspicion and mean-spirited reluctance (in the immediate aftermath of war, the lack of radio commentary to entertain recuperating soldiers caused considerable bad feeling). Television didn’t commence proper regular coverage until the mid-1960s.

Hi, sorry but is there any chance you could direct me to the previous post regarding kickoff times, mentioned above? Many thanks.

http://mtmg.wordpress.com/2006/10/20/sunset-and-floodlighting/

The comments contain the most interesting material.