By 1963, England’s top players would have been well used to foreign travel. They were familiar with the routine and experience of flying, so Ramsey’s first fixture shouldn’t have posed a problem just because it was an away friendly.

But it was an away friendly in Paris, that most unfriendly and unEnglish of cities. It smelt of drains. There were French cars in England of course, but not so many, and not carrying those alien licence plates. And the food, the bathrooms: you can travel a lot further, and feel a lot more familiar.

And the manager was new, and, it soon became clear, quite the xenophobe. He was young, too: nine years before, they’d turfed him out of the England team after that display against the Hungarians. Since then, all he’d done was Ipswich: and, as a look round the dressing room revealed, there were no Ipswich players here. Just the usual blokes, a little louder than usual, sitting a little closer together than usual.

Munich was almost exactly five years ago. Since then, England teams had been drawn from lesser sources than United. Great, gallumphing Wolverhampton Wanderers; ambitious, modern little Burnley; lucky champions Everton. And Spurs, a team of ex-pat Celts plus Smith and Greaves.

Bobby Moore was there, looking like he’d fallen out of a spaghetti western into Duncan Edwards’ boots. He was only 22, and his first England experience had been the 1962 World Cup. He’d been someone Winterbottom had been able to protect from the vagaries of the selection committee. Ramsey had seen him play, well, against Wales in November.

So Moore was in Paris, and it was a disaster, and England lost 5-2. Lose to the French first, said Ramsey’s ghost to the sleeping Capello, and then beat the Germans in a friendly. It’s what Ramsey did, at any rate, but first he got all kinds of things out of his system by losing to the Scots.

Nobby Stiles would say later than Alf Ramsey could get a man to feel like a giant. It was true, but the first player to feel the bad brylcreem roaring through his football veins was Jim Baxter. What was it between Baxter and Ramsey? Slim Jim would always turn it on for Alf, and in Ramsey’s second game, Gordon Banks’s debut, he’d scored twice before half time.

Then came the 1-1 against Brazil, then, as now, a good enough result. But it left England with what amounted to one point out of Ramsey’s first three matches. They’d scored four goals, but let in eight. No one had shone. There was no sign of the “system” of which Ramsey had spoken. Charlton and Greaves, once so prolific, had done nothing.

England would play six more games before 1963 was out. They’d win them all. Charlton and Greaves would produce every single time. Between May and November, it would be played 6, won 6, for 28, against 8.

What happened? Greaves happened… a run of two goals in eight internationals was followed with one of eight goals in five. It would be his last real burst of scoring for England. He wouldn’t have Bobby Smith to play alongside after that. Smith had scored 13 goals in his fifteen internationals and he and Greaves scored 31 times in their 13 games together.

In the 4-0 win over Wales in October, Bobby Charlton’s goal took him to the all-time England scoring record, overtaking Nat Lofthouse and Tom Finney with a total of 31. Greaves was on 25 by then, but although he’d end up with 44, not a single one of the additional goals would make a meaningful difference for England. Charlton’s would kick-start the World Cup, and he’d score more important goals in the ’68 European Championship.

But in November 1963, with only two full years to put together a team for the World Cup, Ramsey’s England was little more than Winterbottom’s, flywheeling on. No new “system” and few new players. It would all change in 1964. Ramsey had been to watch West Ham, and he’d found a new centre-forward, one good enough to become a legend..

But if it was a matter of repeating the 9-3 heroics of 1961, Ramsey could claim to have fallen only one goal short, ending the year with an 8-3 against Northern Ireland. Will those of you in the Catholic seats clap your hands?

Given his inexperience- how did he actually get the job of England coach- the other thing I’ve always wondered about was what his relationship was like with people like Johnny Haynes, presumably as captains lost authority to managers at about this time. Why also was Winterbottom sacked?

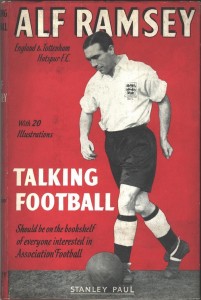

Ramsey didn’t have significantly less experience than the other proposed candidates, one of whom (Adamson) was actually still playing. I suspect that momentum had a great deal to do with it: winning the title with an Ipswich made up of cast-offs and unknowns at the very moment that the appointment swam into view can’t have done him any harm.

Winterbottom resigned after 16 years – he wasn’t sacked, and moved onto another important national sporting role. But his job was split into two: (1) the England manager as we understand it now (2) a post covering national coaching standards and execution. Even after this, however, the England manager’s job wouldn’t be solely to do with the England team until Ericksson. Robson’s last autobiography is extraordinarily telling on this point: his duties spread off in all manner of random directions, and he was given almost no support or resources to go after them.

Looking at the Times archive there were rumours that a Hungarian, G.Mandy, coach of the Israeli national side, had been offered the job on £500/month (which is about £7k to £16k in today’s money). Notable that the Times doesn’t mention any fuss about it being a foreigner.

Btw, and if anyone ever searchs the Times’ archive this will save them the 5 minutes it wasted for me, the Times in that era seemed unable to ever mention anyone’s first name. You would never know he was called Alf or Alfred. “A” or “A.E” was as good as it got when he was selected, and afterwards just “Ramsey”.

Also the Times report says Adamson, Winterbottom’s assistant at the world cup, was actually offered the job but turned it down on grounds of ‘inexperience’.

The report about Adamson is correct, but the Hungarian allegation was a press fiction, possibly aimed, cruelly, at Ramsey himself.

Frankly, the whole appointment process in 1962 strikes me only one way: as profoundly unserious.

Not much has changed over the years then, james!

No; the only serious attempts netted first Ericksson, then Capello. Revie’s appointment WAS taken seriously by the FA’s own lights, but the other names on the list were astonishingly minor ones.