We’ve done it, at last, haven’t we: taken the silent and unanimous decision that Brian Clough matters. He’s made the step up: Brian Clough’s cultural now, gone from the close, sweaty barracks of football because he stands for England like Elgar and Dickens.

The news about Clough isn’t in the tabloids anymore. It’s strictly broadsheet, review and monthly: it’s been to the London Film Festival and must by now be under Granta’s walls, in strength. All that whilst never being out of place: all that, whilst never abandoning Derby, all that without losing the common touch. Clough, more than Ramsey, or Revie, more even than Shankly, his only possible rival, is a cornerstone and comment upon the zeitgeist, and post War Britain is impossible without him.

You can see his shape and hear his voice in all of it: it’s there in the memories of wet bus queues and Tony Blackburn and Green Shield stamps and Sportsnight and the whine of the milkman’s electric float. Clough’s is one of that medley of reassuring provincial voices that dominated Wilson and Heath’s Britain, a Britain that felt so safe but left with a suitcase thirty years ago: he’s there in the head with Jim Callaghan, Eric Morecombe, Jimmy Savile and Noddy Holder. All gone, at least as we knew them then, all towed off in the back of the last Sealink Ferry or municipal dustcart.

Clough, like the others, started out with hack-written biographies and My Lifes. They’re all down in the Bodleian somewhere, still, browning in a stack with a host of others with the same huge type and bad binding and three sets of photos, one in colour. Books about sporting immortals don’t have long lives. The best a given copy can hope for is to be bought, by accident, by a badly-funded public library, where it can lurk at the back unnoticed long after its St Ives-printed brothers have been pulped or landfilled.

Ten years ago, something happened to books about Clough. Or maybe it was something they did, something Clough himself would never have dreamed of: they betrayed their origins. They jumped genre. They became “proper books”, a transformation achieved dangerously close to the disputed border between snobbery and defensible taste and identification. A Clough book would henceforth be a proper autobiography, then a proper biography, then a novel, and then there was a Clough film – which, to show it was keeping up with developments, would feature real actors, and have football in it yet succeed.

Now come the memoirs, and the best of these is BAFTA-winning writer and film-maker Don Shaw’s Clough’s War. Clough’s War, as the title suggests, is Shaw’s first-hand account of the player rebellion at Derby whose ultimate failure brought the great post-1964 rush of English football to an end. After 1973, English club success in Europe covered cracks. It might not have had to. That it did was because Clough was an end, not a beginning; he was the last and greatest product of the only string of good English managers the game has ever produced. That string appeared just as the traditional but resilient business practices that built the game in the late Victorian and Edwardian period were being eased out. Eased out too slowly, too late for Clough: Shaw’s account of a world talent being forced to manouvre amongst petty provincial businessmen, whose sole concern was their local standing amongst their peers, is enough to set your trigger finger twitching back and forth.

Shaw deliberately leaves his picture of Clough incomplete: there are areas of the man into which he can’t see, and he says so. Shaw is a typical Clough friend: outside football but passionate about it, intellectually strong but of ordinary background, possessed of a powerful instinct for, and respect regarding, friendship and loyalty. And, of course, skilled with words. Philip Whitehead, film producer and Labour MP, was another of these Clough acolytes. Had the momentum of the 1960s and early 1970s continued, England would have ended up under the rule of this kind of clever, ordinary northerners and midlanders. 1973 did for that in all sorts of ways: Callaghan gets the blame, for dodging the autumn 1978 election and precipitating Thatcher, but the damage was done in the oil crisis. And, just as much, in the community halls, pubs and discreetly parked football managers’ cars of Derby.

Part of Shaw’s Clough comes across well in this 1979 interview (9 mins):

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oqAZsoF-ghw]

Here, confronted with the young John Motson, Clough displays some of the attributes Shaw notices, describes and frets over:

Fearlessness: “Clough felt invulnerable” says Shaw, “because he knew that the world held him in awe. That is why he could launch his slanderous attacks and suffer no consequences.. Lesser mortals, doing the same, might have expected a smack in the face. Not Clough. He knew that the pedestal on which he stood was high enough to be out of the range of brickbats.”

Self-belief: “I never think of Clough as suffering from megalomania,” says Shaw, “but its dividing line from self-aggrandisement is very close. His reference to Generals Wingate, on the British side, and Patton, on the American, was significant in that their insistence on self-belief, allied to their strong feeling of destiny, was central to their military philosophy, as it was to his approach to football management. His courage was unquestionable. His statement, ‘If I’d been a Spitfire pilot I’d have taken on a squadron of Messerschitts,’ could easily be dismissed as ‘Old Big ‘ead’ bragging. But to have been in his presence when he spoke those words was not to induce intense scepticism, but to accept it, such was the matter-of-fact way in which he made the claim.”

Psychological Aggression: Clough is waiting for Motson to provide him with something with which to disagree, whereupon he will present the disagreement as the product of moral and intellectual failing by Motson and the broadcasters. But Clough doesn’t wait for opportunities to put Motson off balance: putting Motson off balance is the core plot of the interview. In a player, likewise, Shaw says, “Clough searched for character traits and patterns of behaviour, which, once grasped, gave him a power over the player intended to induce fear initially, out of which would come obedience and respect.”

What doesn’t show in the interview are other traits that Clough would bring in to play to help his team. Humour – which he and Peter Taylor would bring deliberately to the table at specific times to reduce tension and pressure on the players – was a big part of the Clough persona, at least until 1982 and the end of the Clough-Taylor partnership. Simplicity: Clough’s advice to his players rarely reached any greater complexity, Shaw points out, than you’d find on a school playing field. Simple things can be remembered in pressure situations, and we saw the principle in reverse during the first McClaren international against Croatia.

Group bonding, brought to a height in the close Derby team, was essential to Clough. During the Ian Storey-Moore debacle, in which Clough essentially kidnapped Moore in order to hijack Moore’s move to Manchester United, he left Moore alone for a chat with each of the first team players in turn. They were quizzed for their views afterwards – “If a guy isn’t liked by the squad, then he’s out”. Moore passed his inspection, so Clough told him, late that evening, “We’re down in the lounge. Come down and have a cocoa with your wonderful mates.”

Nottingham Forest, Shaw thinks, was different: in the end, everything boiled down to fear. At any rate, his relationship with his Derby team represented the height of his career and his life, never to return.

There are sides to these Clough traits which Shaw doesn’t mention but which round out the Clough picture somewhat.

Gaslighting: “Gaslighting” is a technique to put a person off balance. You attribute a thought or feeling to your victim which you cannot know that they have and that they probably do not have. If they deny the thought or feeling, you rubbish their denial. If you are in any sort of authority or close relationship with your victim, this is extremely unsettling for them. The victim starts to distrust themselves, to question the message they are getting from their emotional responses. It slows them down, weakens them. Motson comes in for it constantly, and Clough uses the technique in almost every lengthy interview including the famous Revie conversation of 1974. The point about gaslighting is not just to point out that Clough employed the technique, but to reflect upon what that says about Clough.

Compartmentalizing: Clough didn’t make friends of his players – although he fostered friendship between them. Nor did he make friends on his various boards, or, indeed, Taylor aside, in football generally. This trait is an enabler of other traits: you can’t treat John Motson – or Sam Longson – or a player – as Clough did, and care about their opinion.

Grandiosity: It’s not just in Clough’s words (“..but I’m in the top one.”) but in his manner. Again, with Motson, he interviews like a captured Nazi general who can’t quite believe it isn’t 1940 anymore. Grandiosity needs to be defined in contrast to a sense of superiority: it has an element of defensiveness, of camouflage to it. Reading between Clough’s lines, I sense a frustration at only having football to perform in, a sense of being overpowered for his milieu but of being shut out from the stages that suited his size. Call it an air of frustrated self-importance.

Seeing others only in his own terms: Shaw’s account is one of Clough utilising Shaw’s loyalty, admiration and friendship as political pawns to play in his battle with the Derby board. The board, and the club, exist only as an opportunity for his self-expression. In the Motson interview, he sees the League Championship purely as an exercise in brilliant management, and the quality of the players is a secondary issue. This is the context, I believe, for the various set-piece Clough generosity stories. People for whom human relationships are all manouvre and negotiation, who lack some of the old-shoe moment-by-moment comfortable getting along with their peers, go in for the memorable, exaggerated gesture that the rest of us wouldn’t think of, or if we had, would be too bashful to attempt. Set-piece generosities backlight an otherwise selfish person’s interactions – we assume that they mean well, or that they are “really” generous and the more common selfishness is only an occasional blip of the sort everyone is prone to.

Football success carries enormous social, communal value, and, consequently, it brings with it tremendous forgiveness. The English, like everyone else, enjoy having someone coming from among them who can deliver something worth as much as football trophies. They enjoy having someone as different from most of them as Clough coming from their own stock – even someone differentiated by the sheer quantities of ego, selfishness and bullying as Clough could muster. At a distance, it’s easy to hang onto such personalities other values that the English hold dear – honesty, integrity, etc., and, having hanged hung them, easy to celebrate them: this kind of thing was projected onto the young Henry VIII just as it was onto Clough.

Shaw thinks that Clough’s “management style” and personality could only have thrived at the 1970s Nottingham Forest because only there, and nowhere else before and certainly since, would he be given complete control. I’d put forward a similar argument. Clough displayed many of the traits that apply to the collection of behaviours together known as narcissistic personality disorder. You might share with me my concerns about personality disorders – the way they yoke together what are, after all, behaviours that are part and parcel of human nature, and the arbitrary nature of the yokes themselves. But you’ll also share with me the knowledge of what being on the receiving end of those behaviours is like. Clough, being the man he was, could have succeeded outside football. Both business and politics reward men with just Clough’s traits. But only in football are such men celebrated.

Clough is unusual in football, though, for the sheer range of reasons for celebration and remembrance. His teams played glorious football – both Derby and Forest are still wonderful to watch, even now. His players reached career heights they’d not have seen but for him: perhaps Stuart Pearce was the last of a line that began with John McGovern. He won two league titles, two European Cups, and a host of lesser trophies. He made a football establishment we knew to be inadequate look inadequate, and our gratitude for that has lasted three decades undimmed. He was a great Englishman at a leaderless time, and when Muhammed Ali recognized him, the Champ recognized us all by proxy. I’ve shaken Ali’s hand: I feel I’ve also shaken Clough’s.

He achieved something else, too: something less obvious, less visible to the naked eye, but interesting nonetheless. He did everything with tools left over from another age. To understand this, consider the history of English football management.

Organized football got underway in the 1850s and 1860s. Most sides of the period, playing in the nascent FA Cup, were managerless teams of friends or teams put together at universities or military institutions. The team captain was also the team convenor, the man who knew everyone, could contact everyone, could bring everyone (or nearly everyone, in amateur days) together for matches. Personal acquaintance with the team was the key to playing for the team.

Teams of this type were to all intents and purposes unstaffed. There was no trainer, no doctor, no physio, no kitman. What changed this was the game’s own development. Early international teams – take, for instance, Quintin Hogg’s unofficial Scottish side of 1870-1, made up entirely of London-based Scots – were like club sides, comprised of friends and acquaintances. As the number of clubs increased, and with it the number of serious players, acquaintance became increasingly second hand, and a player would be picked for England or Scotland on the strength of reputation and word of mouth, not always personal knowledge.

As the number of teams based in the north of England multiplied, this became more complicated. A Blackburn Olympic might play southern teams twice in a season, perhaps three times, and only in the FA Cup. Knowledge of Olympic players amongst the men picking the England or Scotland teams was limited.

But with the northern teams charging for entry to their matches, the likes of Olympic, or Preston, found themselves needing to produce elevens of the sort of quality that might attract a crowd. That sort of eleven wouldn’t be made up of people the captain had heard of, but of people a crowd would come to hear of and talk about, or that a newspaper might celebrate. Very quickly, the logic of the situation demanded that a northern club have on its staff someone who had knowledge of players from a wide area, and the ability and desire to expand that knowledge faster than his colleagues at rival clubs. And, with entry fees being charged, and then, wages being paid, some business skill might come in useful. Thus the secretary-manager was born.

Within twenty years, the secretary-manager was a standard, accepted figure at every major football club in the Football League, the Southern League, and the other professional leagues. John Cameron, writing in 1905, described the manager’s duties as

- the acquisition of a decent first XI

- keeping the club’s accounts up to date

- managing the fixture list

- administering the stadium (maintenance etc)

By this stage, and no doubt as a result of the time constraints upon the manager, a second accepted figure had emerged: the trainer. Cameron describes the trainer as

regarded as the father of his side. Attending to the players’ smallest wants, dressing their injuries, rubbing them down, hardening their muscles, and freely giving advice in a thousand matters, the occupation of a trainer is a busy one.

Only by his efforts and shrewd judgement the appearance on the field of a popular player sometimes depends. Mistakes result in crippled players, and cause vexation of the spirit to the club’s officials.

In the space of barely thirty years, clubs went from being loose associations of mates to being joint stock companies with full-time staff. But very few full-time staff: it’s interesting to contemplate a club with a squad of twenty, plus manager, trainer and turnstile staff, weekly being confronted with crowds of twenty, thirty and forty thousand people. Such disparities had been seen only at the quiet branch stations serving the likes of Epsom, and then only once or twice a year. An Everton or a Tottenham were now handling them every fortnight, and without a railway company as backup.

Something stalled in British football when play halted in 1915. Crowds would continue to grow in the 1920s and 1930s, but the only signficant change in the way clubs were run would be tactical, Chapman amending the traditional 2-3-5 in 1925 to cope with the altered offside law. Manchester United went through the 1950s with four core administrative staff. Around the great league clubs of the north, industry and its management was transformed, by the arrival of the modern assembly line, by the arrival of efficient road transport, and by the impact of successive education acts. Football management stayed the same.

So, when Clough arrived at Hartlepools, Peter Taylor had to begin by masquerading as “trainer”, despite having even less relevant knowledge than his sponge-wielding peers. And, at Derby, his appointment was the cause of the first of Clough’s many conflicts with Sam Longson.

During the great years of his management career, in other words, Clough was, to all intents and purposes, a secretary-manager (Derby appointing “secretary” Webb only after a financial scandal caused by Clough’s indifference to the demands of accounting). Clough was in an Edwardian role. So were his English counterparts. But his European rivals were not.

Clough’s attitude towards team and tactics were Edwardian too. John Cameron, in 1905, might have been speaking for Clough in 1973:

Every manager is aware that if a professional team is to show successful results there must exist a genuine spirit of good fellowship among the players. The little jealousies that sometimes occur between different members of a team are unfortunate in the extreme, and should on all occasions be firmly repressed by those in authority.

Cameron never discusses tactics, and we know from other Edwardian writers that the basic 2-3-5 was considered to be the optimum formation, arrived at organically through experience and experimentation. Don Shaw describes just such an attitude in Clough:

Clough disregarded ‘tactics’ which, he said, were ‘the best thing to talk about if you want to ruin a team’s rhythm.’ Blackboard analysts were condemned as counter-productive. ‘Tactics aren’t for me,’ he declared. ‘They’re things teams dream up because they’re scared they might lose.’

Here Clough is channelling R.S. McColl, the Edwardian footballer and founder of the newsagent chain, who wrote:

Too rigid a system of play, in which all the moves are known, will not do. There must be flexibility; endless variety and versatility; constant surprises for the other side. System must be inspired by art and innate genius for and love of the game.

“We pissed all over Benfica,” said Clough after putting McColl’s advice into practice in the European Cup. “You don’t teach genius,” he said on another occasion. “You watch it.”

Clough’s Hartlepools and Derby were built around the Edwardian idea of the primacy of the first XI, not on the later squad concept first properly seen in England in Paisley’s Liverpool side of 1976-8. The essentials were a good goalkeeper (e.g. Colin Boulton), a good centre-half (e.g. Roy McFarland), a good link man (e.g. John McGovern), a good winger (e.g. Alan Hinton) and a good centre-forward (e.g. John O’Hare). The rest would follow.

Clough’s achievement, then, was to take the Edwardian-style football club to the very highest level of play and achievement that the structure offered. At a time when the frozen administrative set-up of British football was so obviously eating into British football’s future, and making clubs like Derby look like museum pieces put next to Benfica or Juventus with their tactical sophistication and modern stadia and evolved youth policies, Clough made it all work, one last time.

Like Cameron, like Chapman, Clough was a narcissist fuelled by his self-perceived superiority over the men he worked amongst. It took that unusual, splintered, often unpleasant and unnegotiable personality to pull success from such an unlikely hat as the Edwardian-style football club. Men like that can and do succeed elsewhere, in politics and business. But only in football are they truly celebrated.

Because England never came for him, there is a sense of something missing from Clough’s success. And the success he did have, vast as it was, helped to sustain the illusion that there was nothing wrong with British football, that all we had to do to catch up with Holland, with Brazil, with Germany, was find another Clough, another man who could crank the same rusting handle as hard as he had been able.

But we haven’t found another Clough. He was the last. Joltin’ Joe has left and gone away. Perhaps his greatest tribute is the sheer scale of the silence he’s left behind him.

Brilliant, brilliant article. This is one of your best James- in a sense I wonder if anyone who didn’t have the kind of personality of Clough (and his contemporaries) could have survived that role. One of the other fascinating issues to me is the evolution of Clough- all the films and the books concentrate on the seventies but it would be interesting to look into the eighties and the nineties. Incidentally on a last point- could you argue that Stuart Pearce was the last fully formed player- but the last great Clough player to seize English football was Roy Keane who exemplifies a kind of transition from the managers and dynasties of the seventies eg Liverpool to those of the nineties.

A marvelous piece, James. The next interesting question might be about those who managed Clough at Middlesbrough and Sunderland. What did they tell him and how he reacted. What he took forward and what he rejected.

It’s also interesting that Clough’s success comes at the end of what is sometimes called the ‘me’ decade.

God knows what I am doing reading this today of all days, mind. Still it is very good to read.

Fantastic, James. As a 26 year old, I missed out on Clough in his pomp, but it’s great to read articles like this which put his influence in context and flesh out the bones of the countless quotes and vox pops in the archives.

Really I expect to have to pay to read stuff as good as this, James. Just in case it has occurred to you to use this piece as a sample while looking for a paying gig, may I point out that you say “Both business and politics reward men with just Clough’s traits. But only in football are such men celebrated” (near as dammit) twice. I invite you to edit it, bin this comment, and try to flog your wares. Bon chance.

This is beautifully written, James. Absolutely tremendous stuff.

I would say, whilst Clough was undoubtedly talented, there seems to be a media loop about him and Shankly. They were both intriguing, obstinate, brilliant geniuses with a gift for a quote and the ability to wow a room of journalists with both their charisma, their (at times) bizarre behaviour and the football their teams put out.

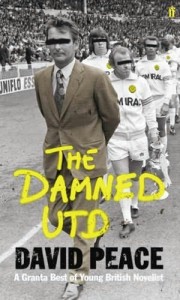

D. Hamilton has written his book, the Damned United has been a best-selling film (and book) and he is rightly praised in many a media piece.

I suppose, my question is, why not Paisley? Far more successful (taking a decent team and making them into the best in Europe over an extended period not seen since Real Madrid’s days and – I’d wager – not since) than Clough and Shankly but not as camera friendly, not as media savvy and not as interesting for biographers.

RCM

http://leftbackinthechangingroom.blogspot.com

James, congratulations on a very well written piece, as a Nottingham Forest supporter I had the great fortune to meet the man on several occasions and I can attest to his generosity. I think he claims more column inches than Paisley or Shanks purely because he managed to take not one but two provincial teams to the top of the English game, the second of those went on to win the top flight and two European cups in successive seasons. He also knew how to use the media to his best advantage. A great man, sorely missed.