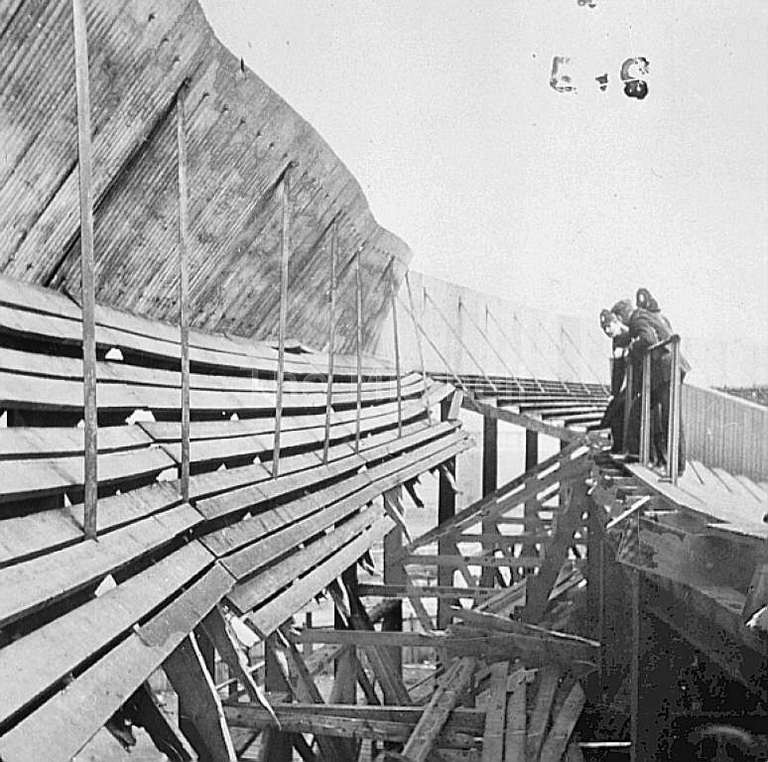

Later, they blamed the rain for bringing the stand down. The eventual toll from the accident on 5 April was 25, but the deaths took time: the stand collapsed on a Saturday, and by the following Wednesday the count was still only 21. (More beneath the cut)

The accident took place at a Scotland/England international in front of an estimated 70,000 people. Most of them would have been standing spectators, and it jars now that most of those present didn’t notice the gravity of what had happened. The Scotsman reports that only fears of riot forced the organisers into continuing with the game, that behind the scenes the Scottish and English Football Associations had decided by half-time not to count the game as an official international in respect to the dead.

There was a riot anyway, and mounted police had to drive the spectators back behind the iron fencing. The game finished in a draw, and, honour satisfied, the Associations restored the match to the canon.

The telephone was in its twenties by this stage, and within 36 hours of the accident, English clubs were offering themselves for charity matches to raise money for the bereaved. Blackburn Rovers came north to play Celtic. Scotland’s reaction was a mixture of shock and grief: for a week after the accident, the newspapers cleared what space they possessed for bulletins about the injured, reports of funerals, wires received.

Only the Scottish churches got it wrong, and then only at official distance. On the Wednesday following, the Scotsman reported:

At a meeting of the Synod of Glasgow and Ayr in the Tron Church, Glasgow, yesterday, the Moderator – the Rev. Andrew Laidlaw, St. George’s-in-the-Fields – made reference to the disaster at the outset of proceedings. He said he wished to express their sympathy and sorrow with those who suffered in the appalling calamity which befell the city last Saturday. Oftentimes they had expressed from their pulpits their regrets for the excessive pleasure-seeking of the younger generation, and their detestation of the rudeness and the bad, often blasphemous language which was too frequently heard in the crowds of those who attended football matches, and the betting and other evils which were said to abound. Very startlingly the pleasure-seeking crowd had been awakened to know that in the midst of life they were in death, and he would repeat in the words of their Master, “Be ye also ready, for in such an hour as ye think not your Lord cometh.” To those who had been so sorely bereaved, he was sure they extended their heartfelt sympathy, and for those who were lying on beds of pain they prayed that it might please Almightly God to restore them to health, and to spare them their lives for faithful service and the reward of a blessed life.

I know; Christ. But note the tone, because it was a vitally important one in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain. Most of the reformers of the day – the likes of Booth, Mayhew, Rowntree, the Webbs and the Fabians – were agitated by poverty and poor living and working conditions not because they were inescapable and unpleasant, but because they were  a threat to the moral lives of the people.

This fear – that the industrial cities, huge in the north and new to history were bad for the souls of their inhabitants – found many outlets. By 1885, there’d been 20 years of attempts to control urban prostitution through the Contagious Diseases Acts, and these had prompted some of the first concerted urban working class political actions and protest. The abolition of the Acts in that year, the same year that saw the proper arrival of professional football, was followed by a decade of attacks on brothels. And by a surge of syphilis cases. (In 1958, Italy tried the same thing: syphilis rates doubled within a couple of years).

The same fear had prompted the exportation of football from the public schools and universities into the urban north. Churches saw the game as a means of bringing the values of Arnold and Hughes to the masses; factory owners thought of it as a means to keep the men out of the pub.

Unintended consequences: football in Glasgow would engender crowd violence, gambling, drunkenness and, to this day, an imbedded religious bigotry and racism towards Irish Catholics and from them. Â Yet to this day football writers and watchers expect the game to engender something, to embody magnificent values. It’s supposed to carry within it something of a Britishness – the kind of Britishness that divides, for instance, a Tevez from a Ronaldo. We know what that means; we understand it, and look for it. There’s a Scotch churchman glowering inside even the best of us.

POSTSCRIPT:

A propos a certain kind of Britishness, which British international forward peppers his autobiography with references to Hemingway and his own love of Spanish bullfighting? No prizes, just the usual MTMG quiz kudos.

UPDATE: The 1901 census throws up the interesting news that Herbert Chapman was a clerk at a Welsh colliery in that year. But he wasn’t: he was playing for Worksop Town and studying in Sheffield. Or something: there’s no evidence that he ever lived or worked in Wales. So why? etc. and it’s another hint that here is a far more interesting man than his journeyman biographies reveal.