What British football had become by 1905, the world game reflects now. League systems, knock-out cups, international matches, the basic rules, professionalism, the nature of the football club, football administration – they’re all British inventions dating from a hectic 42 year period beginning in 1863 with the formation of the Football Association.

But in the 42 years after 1905, there is only one innovation to add to the list, and it’s a minor one, not universally adopted: the Buchan/Chapman third-back game. British men were responsible for innovation abroad – see the excellent El Bombin site for more on this – but Herbert Chapman’s many other frustrated ideas aside, the domestic game goes quiet.

In the subsequent sixty years, we’ve become wholesale importers of ideas and trends – some good, some not so good. We have exported Bobby Robson and hooliganism.

It’s worth asking why this is so. When English thinking has changed the design of rugby union kit in the last decade, when English cricket has invented the 20-20 game in the last decade, when British designers have dominated Formula One racing – it’s worth asking what happened to our national game to make it such a passive affair, content to jog along behind.

What follows are ideas, not conclusions: have at them.

The end of Britain’s industrial dominance

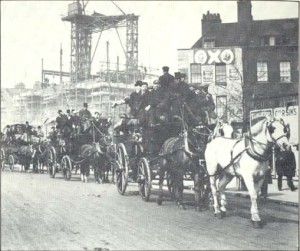

Industrialisation happened to Britain first, and had the effect of creating in short order a large number of large towns and cities with new wealth and few traditions of their own. Football clubs appear in these places as soon as the first shoots of reform free up time and energy, when there is enough of a railway system to make competition possible, but before suburbanization pushed available clear land out of range of the high-density inner cities.

By 1914, that development had run out of steam in many respects. The railway network had peaked, leaving no new territory that could be opened up. The industrial north, changed out of all recognition since 1840, would remain in its essential Edwardian form until World War II. The football clubs of the north would do likewise. They were born in innovative places, and stagnated in stagnating ones.

Football was an entertainment, not a sport

Once the idea of the large football stadium had been made real, starting with Everton’s Goodison Park, it found its typical form very quickly. Today, as in 1905, there seems to be a maximum crowd size of 60-100,000. Beyond that, the fan is too far from the pitch. Pace television, that imposes an upper limit on the income available from playing matches – and, as a maximum wage had been imposed by 1905, it imposes an upper limit on what’s worth building. There are few significant new stadia built after 1914, and no extensions of capacity beyond that maximum.

Most of the changes seen between 1863 and 1905 had served to create the situation in which football could perform as a mass entertainment – the standardization of rules, the incorporation of professional players, the creation of competitions. Once this was done, the question of why the game should continue to change became moot. The next major change – the loosening of the offside rule in 1925 – came because the status quo was not providing the same entertainment and football, already an expensive option for working and lower middle-class men, was facing strong competition for its audience.

British international dominance

South America and Europe caught up with Britain because we were there to be caught up with. We allowed ourselves to be caught up because we were ahead for a very, very long time, and our psychological advantage endured for a good twenty years after that. Since 1953, we have never regained the lead, but we have kept the rest of the world sufficiently in sight for the situation to be relatively painless. This is because of the relative strength of the Football Association and domestic football structures which have shown incredible resilience over the years and have kept standards up to a level above that which would trigger drastic remedial action.

Education

That first generation of professional footballers were, perhaps not entirely coincidentally, the first generation of working class people to undergo compulsory education. As a result, there were a large number of highly intelligent men playing professional football – the kind of intelligence that white-collar work and red-brick universities would claim in ever increasing numbers in subsequent years.

Because the idea of football as a lifelong career didn’t exist as it does now, few of these men remained in the game. Those that did – and Herbert Chapman is the supreme example – did not have successors. Edwardian football was a home to the intelligent and articulate; these people would find better homes in later years, the game itself undergoing a brain drain that has never really gone into reverse, not even now in an age where footballer’s wages dwarf those of white collar professionals.

Significant numbers of the great postwar managers – Busby, Shankly, Paisley – came from Scottish or north-eastern mining stock, areas where white-collar escape remained difficult longer than in the big industrial cities. Others – Clough, for instance – failed to take the opportunities of their education.

Football’s economics after 1914 limited the need to think and innovate – the run-on from educational reform meant that there were ever fewer people in the game able to do the thinking.

Gentlemen and Tradesmen

The traditional British idea of the gentleman – not sullying his hands with work – lives on: the dream of the country house and the ownership of land as the ultimate goal of the approved British life is as powerful now as ever. British sport has a version of this – most recently seen in the resistance to professionalism in Rugby Union. Games are for enjoyment, not to be taken seriously; training spoils the fun. And that British nostrum, “don’t be clever” converts into a sporting “don’t be skilful” – unless you propose to justify your skill in the manner of a Best or Gascoigne, that is.

In short, the very idea of improvement, of innovation, is suspect in the British game and always has been.

Alongside that is the determination – the tenacity of the idea – that there are such things as English or British values and that these are more important to victory than skill or intelligence. “Passion and commitment” in short. The Australians, who show both of those qualities in spades, disagree with us, and want intelligence and strategy too. We don’t: witness the steady, stealthy writing-out of Clive Woodward from the English memory of the 2003 Rugby World Cup.

Those who are keenest on the “passion and commitment” idea think themselves the salt of the earth; in reality, they are the dupes of snobbery, ignorant of their need of Langland’s advice and prisoners to an invisible, Austenesque social snare.

Homophobia

The rest of British life has benefitted from the cultural, economic and moral energy released by the horribly belated correction of moral attitudes towards homosexuality. I don’t know why the hell football doesn’t want that too, other than its usual reasons of childish, sniggering cowardice. Football is prone to mistake intelligence or creative thinking for homosexuality and to see that in a negative light.

Feminism: repeat to fade. Poor Jackie Ashley.

Football has done a great deal to fight racism in Britain – perhaps that deserves the term “innovation” in the light of recent experiences in Spain, Italy and Eastern Europe. That it felt it to be in its own interests to do so doesn’t take away from the courage shown by the pioneers who set that change in motion thirty years ago. But in relation to other things, it can seem anomalous.

Coaching

The Premier League’s coaching certificate is a qualification that you cannot fail – all you need do is put in the hours. Isn’t that extraordinary? but it comes from a tradition that insists on coaching, if it really must take place, mustn’t be too clever and must come from the heart, from natural talent, not from actual learning.

On Radio 5’s 606 last night, a Chelsea fan urged the replacement of Avram Grant as manager by Kerry Dixon and Gianfranco Zola. In British football management circles, you have to have been a horse if you are to become a jockey. Wenger, Mourinho and Benitez, none of whom played top level football, are living arguments to the contrary, but this conundrum has a habit of failing to impose itself on the national sporting consciousness.

“The lads in their wisdom,” in Gordon Strachan’s phrase (used after his Coventry City side ignored his instructions and took a beating) has always been the attitude. Edwardian football didn’t have managers in charge of tactics and strategy until Chapman, and there haven’t been that many in truth since. Foreign managers working in Britain or with British players complain at the lack of interest in matters of tactics, of strategy or problem solving, something exemplified by the difference between Sven Goran Ericksson’s approach with Manchester City compared to his treatment of England.

Conclusion

The British game that grew out of industrialization was an entertainment, not a sport: it was “only a game” albeit one with serious life lessons to teach. Once it found a viable form, as it had by 1905, the season in which the six-yard zone ceased to resemble breasts, once it was making as much money as was possible, why change, and how?

The British were top dogs at football for a very long time – and have never been so very bad at it as to feel the need for any significant alteration in their approach to it.

Football was, and perhaps still is, badly positioned to attract the active interest of the kind of British person who is responsible for the UK’s reputation for ideas, inventions, eccentricity, Clive Sinclair and Beagle II. But it’s good at engaging the interest of the type of person who hates all that sort of thing. Wodehouse divided humanity into golfers and poets. Football probably thinks Wodehouse was a ponce.

But football’s a frightened little lad in an overlarge body, laughing too loud at the rest of the world with the boys in the crowd, and the cheap words still come too easily.

What do you think? Nonsense? What other angles of this deserve coverage? Did British football cease to innovate?

What non-tactical innovations would you lay at the door of foreign football after this time? Floodlit games, all-seater stadium, the European and World cups, that sort of thing?

On the business side of things, however, I think that the UK has been the real engine of innovation in Europe. First to seriously monetise the TV audience, first pay-per-view league (I think this is right), first to aggressively market in Asia, first to make substantial use of agents, first stock market flotations of clubs. The creation of the Premiership also probably falls into this category. I suppose one might regard a lot of these innovations as baleful, but they’ve certainly caught on.

I’d add El Tel and El Tosh to Bobby Robson by the way.

Venables, Toshack, Roy Hodgson, too Sows ears to silk purses everywhere but England.

I don’t think dsquared is completely correct. Italian football seriously monetised the TV audience long before English football did. The greatest teams of the Berlusconi-Milan era came precisely out of the fact that the Italian league had out monetised everyone in Europe (including England) at the time.

Likewise, there were pay-per-view arrangements in Germany and I believe in Spain before we took the plunge in 1999.

Asia? Yes, although Real Madrid did put some of the hard yards in there too. And to some degree it’s backwards to think of it as “English innovation” as it was mostly the product of Asian TV executives and the fact that the EPL was already beginning its commercial ascendancy in Europe at that time.

Agents? South American and Italian and Spanish football pioneered almost every aspect of that around Maradona and others.

Stock Market flotations? Yes. We do lead Europe in that, not just in football, but in most spheres.

I’d lay some of the tactical/coaching issues at the door of the “biggest professional system in the world.”

When you have 92 (or however many) professional clubs you have a large system which like many others tends to become insular. Thus, while in other countries, coaching in particular was cross-fertilised by experts from other sports, here, wisdom was that you needed to be “in football to understand football.”

There was no “National Sporting Institute” in England, to help bring insights from athletics and other sports. We only got professional fitness in, largely via foreign coaches like Wenger.

What’s interesting is why Stanley Matthews (for example) didn’t have more influence on the training culture?

For me the aversion to tactics comes as much as anything out of the aversion to skills. Obviously, “Total Football” is a tactic that relies on particular skills, but just about every formation innovation has required a better range of passing than seems typical in the English game.

There’s something about spatial awareness in there too. What’s notable about the national team is that players seem to function very badly when asked to do something outside of their club role. Part of that is bad attitude and lack of flexibility in the mind, but part of it is to do with the way we train skills.

You might as well ask why the English working class has always seemed to be opposed to education, when the Scots, Ulstermen and perhaps the Welsh too, have been more interested in it.

I’m not sure about dearieme’s comment either. In the North of England at least, working class culture was as education focused as in the other countries of the United Kingdom.

And arguably at least, the early history of the game is at least in part a history of a few Southern clubs in a Northern milieu… The question becomes, what’s the difference between the coal mining communities of the North or the ship-building communities of Scotland and NI and the car factory towns further South?

But I think that’s straying a bit too much. Whilst football attitudes are of course rooted in societal ones, it’s more valuable to concentrate on the interaction between the two, because that’s where change is still possible.

(James says) I wonder if the key difference between the coalmining communities of the North – and I’d roll in cotton towns too, here – is simply that they came first, and, of the mass games, football came first. It’s my impression that, further south, 20th Century industries supported football clubs, but not on the same scale, and in competition with e.g. the sport that worried Herbert Chapman, speedway.

I think Milan’s financial strength always came from their huge stadium rather than TV rights didn’t it?

I don’t have the document to hand, but Umberto Lago (sp?) wrote some stuff about the impact of TV money in Italian football. It’s true that the first wave of Milan success (pre-1990) came out of some talent spotting and Berlusconi’s personal spending.

Lago argues that what allowed them to pull away domestically (although they only won 1 out of the 4 European Cup finals they reached) was the money stream out of TV, partially pay-TV deals, but also more complex arrangements within the growing Berlusconi media empire. In that way at least you can argue that at that time they are where teams like Man Utd still only plan to be in a few years time when they break out of collective Premier League bargaining: as much media content arm of a larger media empire as football team.