The first edition of James Corbett’s “England Expects: A History of the England Football Team” has sat somewhere near my desk since about a fortnight after its initial publication. There hadn’t really been a proper full England history before. Of course, there’d been books about England managers – but that’s not quite the same thing, and in any event, by the time Ramsey was appointed, the first proper England manager as we know them, English international football was already 90 years old. So Corbett’s huge red hardback, which combined concise match reporting from the very start, concentrated on players and audience as much as managers, and in sharp, clean prose avoided all of the usual laddish clichees, was extremely welcome.

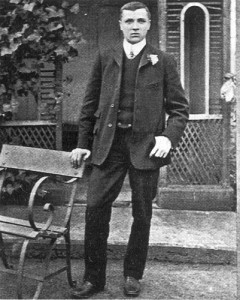

The second edition is a reillustrated, tightened-up paperback, and it gives a reader confidence when a photograph of Edwardian striking star Steve Bloomer is captioned author’s own collection. For James Corbett, the first half century of international football – 1870-1920 – isn’t the usual source of sneering fun, and his account has none of the usual sense that writers give of waiting for the real business to begin. So this is the best short account of the amateur-versus-professional controversy. The wealthy pioneers like Lord Kinnaird are proper sportsmen, not moustache-twiddling sexual obsessives. Snobbery is not the only reason keeping the Football Association out of FIFA. Professional league football is not the usual unmitigated triumph for the working man. Corbett lets the game grow in its own time and context, and that time and context are assuredly not ours.

Even non-fiction accounts, when done properly, fall into one or another of the seven plots, and there’s an enjoyable debate to be had about which one the England football team follows and at what speed. The usual unconscious pick of football writers is decline, fall, recovery, triumph! fall again, recovery, Gazzamania, and (insert blur of journalism to bring us “up to date”). Corbett avoids this. The inter-war period, badly filmed and so little-known to most fans, is closely covered without distracting references to past and future, making good use of what are actually fairly extensive primary autobiographical sources. The great England side of the war years and after – Lawton, Mannion, Matthews, Finney, Carter and co. – are recorded and celebrated for their own sake, not for that of Hungary and 1953.

Not that 1953 came out of the blue: Corbett incorporates it into a longer account of relative decline after the wartime side broke up, and remarks that the 6-3 defeat itself caused less upset amongst the game’s players and administrators than you might think. 1950-55 was one of a number of the fallow periods that England’s team have passed through – the 1920s, either side of Dixie Dean, was another, and so was 1975-80, and 1991-5. How would the Hungarians of ’53 gotten on against the Byrne-Edwards-Taylor England of 1957, or the Charlton-Greaves England of 1962? England’s recovery after the 1954 World Cup, in both club and international terms, was real enough, and Corbett’s chapter about those sunnier last years of the Winterbottom regime is headed by a fine meditative photo of Stanley Matthews besuited, new holder of the ballon d’or, gazing into the future from the sand dunes at Blackpool.

That future would be one in which England built three separate teams, in the space of twelve years, which were capable of frightening anyone, even the 1970 Brazilians. Three good sides – without revolutions in training, without changes to the league system (save the scrapping of the regional divisions in favour of a national Division Four), and without reform at the FA. Some things had changed: the ’57-58 pre-Munich side were the best nourished in history, thanks to rationing, and, thanks to education reforms and Walter Winterbottom, many of the ’66 and ’70 sides had received proper coaching in good conditions at school at the right age. But the biggest change of all was the ending of committee selection, partially under Winterbottom and finally under Ramsey. Corbett’s long, detailed examination of Ramsey’s construction of the ’66 side against strong and vocal opposition is the deserved highlight of the book. If you want to know what the verrou system is, you’ll have to buy a copy.

What follows ’66 is a kind of flatlining: the endless, exhausting efforts to do it again, to retrieve some footballing self-esteem, all while the game goes on about its own, quite separate business elsewhere. There are ways to make sense of this. It comes back to plot again: and Corbett, confronted by the triumph/disaster dichotomy that night/days its way out of the mouths of fans and journalists, opts instead for theme:

the insatiable burden of expectation facing our footballers and the way they have often been overwhelmed by it..shattered dreams and unyielding expectation (stretching from) origins among the mid-Victorians through to a modern era defined by money, massive egos and chronic underachievement(..) the monstrous expectation.. rears its head again and again and in so many different ways. There is, alas, no happy ending.

But there is happiness along the way. Hudson’s match in 1975 against West Germany; Keegan and Brooking’s attacking 2-0 Wembley win over Italy two years later; the vindication of Bobby Robson and Alan Shearer’s romp in the sunshine against Holland. Before that game, Terry Venables summed it up: “We are inclined to be a nation (which thinks) we are the worst team in the world or the best. Neither is true.”

The final chapters cover England’s progress during what will have been the period of James Corbett’s own writing career. Unlike many journalists, he’s resisted the temptation to place himself at the centre of events, appearing only when doing so adds an essential psychological point (Corbett’s meeting with Steve McClaren six months before the future Eredivisie winner’s England sacking for example). Nor, while writing about the unbearable expectations placed on England, does he overpromote the issue: what keeps us interested, in the end, isn’t expectation, he says, but something lighter and better: hope.

England Expects is fully footnoted and contains a comprehensive bibliography and is published by De Coubertin at £12.99.

Excellent review James – and one that means I have added it to my holiday reading list.